Main topics: Journalism in crisis, characteristics of traditional journalism today, competition, digitalization, 24-hour news cycle, negative framing, the brain’s processing of the news, perception vs. reality, consequences for individuals and society, Audience needs and wants from the news.

Summary:

Digital disruption has resulted in an economic crisis for the news industry. At the same time studies have shown that people are becoming more disengaged from the news. A constant barrage of negative, conflict-based coverage has resulted in a large percentage of people tuning out of the news as it makes them feel depressed and helpless. The overwhelming negative nature of news coverage has led to skewed perceptions about the actual state of the world. Trust in the news media has fallen over the years (although it rose some during the COVID-19 pandemic), which has grave ramifications for societies. Surveys have shown that audiences are not getting all they want from media outlets and journalists need to rethink their coverage so that their reporting stays relevant to their communities, opens up new paths to economic sustainability and contributes to positive change.

Independent, quality journalism plays a crucial role in democratic societies, informing people about the political, economic and social developments in their countries. This information enables them to make informed decisions in their daily lives and who they vote for in elections. Good journalism holds the powerful to account, uncovers corruption and wrongdoing, spotlights the workings of government and the economy, looks honestly at societal trends and serves as a guide for people during times of crisis. But today, traditional journalism is experiencing a crisis of its own, perhaps even an existential one. Trust in the media has been sinking, people are choosing to shut out the news, and digitization has led to revenue streams at media operations drying up, forcing newsrooms to cut staff, ramp up output at the expense of quality or shutter their operations all together.

The COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated a decades-long trend of newsroom lay-offs, newspaper shutdowns, dwindling resources, pay cuts and reporters generally asked to do more with less. The pandemic brought about a new wave of closures, layoffs, furloughs and salary cuts across the globe. A number of studies have documented the difficulties facing the news media in the US, Canada, India, Europe and beyond. While there are some bright spots, with innovative projects and reporters working hard to fill the gaps, the overall picture is not a pretty one.

There are a variety of factors, beyond the pandemic, contributing to journalism’s plight, which we will explore in more detail below.

Digital disruption and an ever-faster news cycle: Changes in journalism and digital disruption have led to changes in news delivery and news content. The internet has made publishing easier than ever and led to an explosion of news outlets, many online, and done away with traditional news cycles (12 or 24 hours for print, maybe hourly for radio stations). Now news and updates can be published 24 hours a day, seven days a week, on websites and social media. Cable TV news is a 24/7 operation. People have more information options than ever before, which has led to a war for the public’s increasingly fragmented attention. Strategies the media houses have adopted to grab that attention include:

Yet these strategies don’t appear to be working in the long term. They haven’t helped bring journalism out of its current crisis. In fact, as we will see below, they often have the opposite effect than intended.

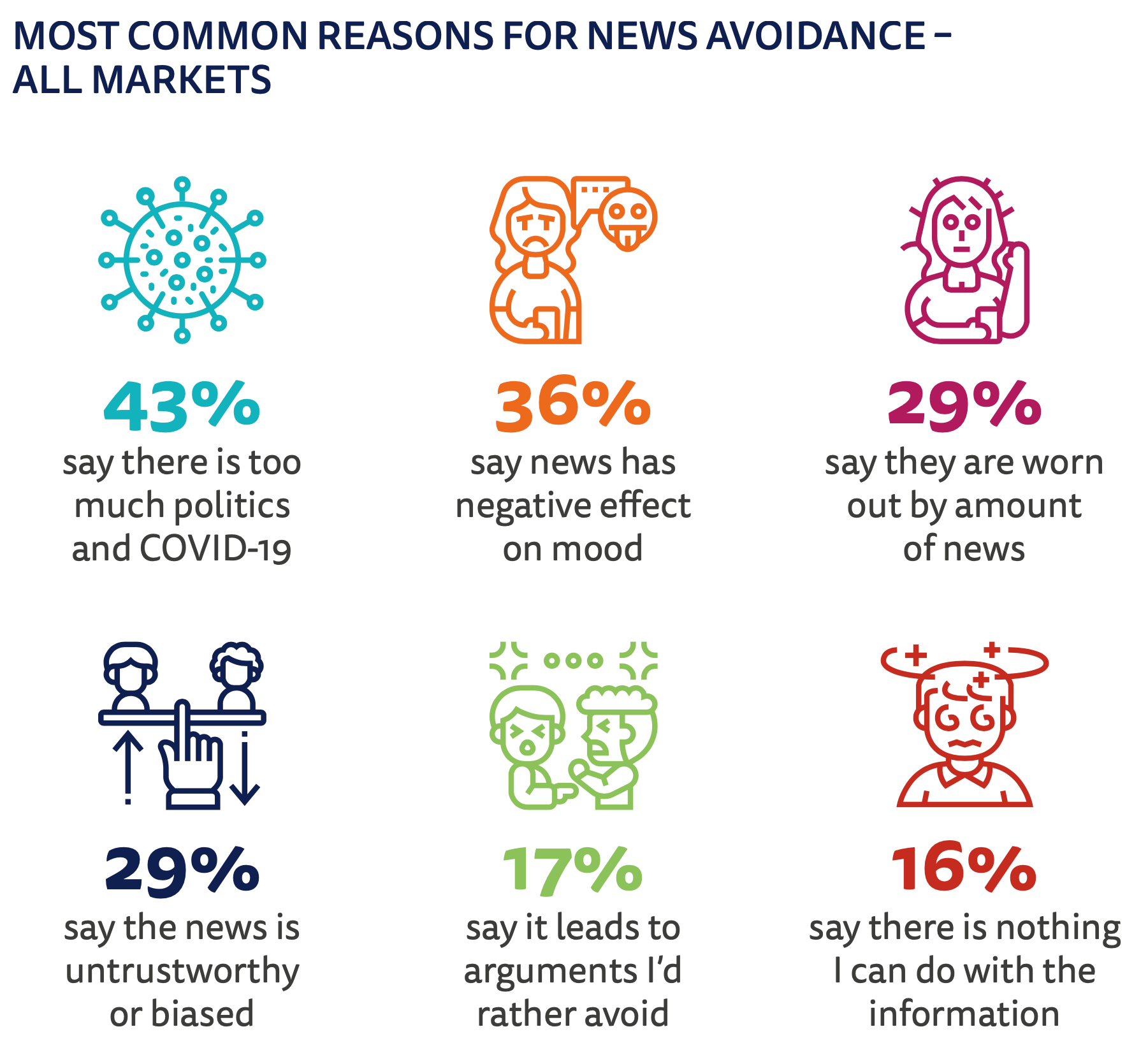

News fatigue/news avoidance: For several years, greater numbers of people have been actively turning away from the news – tired or angry at what they see. Turning off the TV news program or avoiding a news website is a way to shield oneself from the unrelenting barrage of negativity that can have an impact on people’s mood. A 2022 survey in 46 countries by the Reuters Institute (Digital News Report 2022) found that 38% of respondents said they actively avoid the news. That was up from 29% in 2017. Those surveyed said they avoid the news because it has a negative effect on their mood (36%) or because they feel powerless to change anything for the better (16%). Previous studies have shown that women and younger generations are especially allergic to the “noise” of a news cycle.

In many parts of the world, the COVID-19 pandemic revived interest in the news as people turned to trusted news sources to make sense of the situation. However, as the virus continued to dominate the headlines, audiences began to turn away from the unrelenting negativity and focus on fatalities and rising infection rates. Despite the pandemic bump, the proportion of respondents saying they are very or extremely interested in the news has fallen by an average of five percentage points since 2016. Among 18-34 year olds, 41% sometimes or actively avoid the news. Many young people want more diverse voices and perspectives and are looking for stories that don’t depress and upset them.

Source: Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2022

Trust deficit: The Coronavirus pandemic resulted in rise in trust in the media, but new research finds the trajectory is headed downward again. Before the pandemic, in 2019, only 42% of those surveyed trusted the news, down two percentage points in two years. That rose to 44% in the 2021 Reuters Digital News Report, but has fallen back to 42% again. Trust in individual news brands is trending downward in most countries.

Trust levels vary in different countries and in different regions. While in Thailand more than one-half of people trust most media most of the time, in India that number is 41% while in the Philippines it stands at 37%. In the three African countries analyzed by the Reuters Institute, trust is still relatively high by international standards: 57% of Kenyans trust most media most of the time (58% of Nigerians, 61% of South Africans). No country in the Middle East is covered in the Reuters study.

Lack of representation (diversity and inclusion): When communities don’t feel represented in the media, they tend to feel less engaged and stop trusting the news. The 2022 Reuters study found that a majority of 18–24 year-olds in Western Europe feel they are not fairly represented in the media and that there is too little coverage of issues they care about. As a result, four in ten in this group say that social media is now their main source of news.

Many media outlets in the US and Europe have started hiring members of underrepresented communities to work in their newsrooms. But a diverse newsroom does not automatically lead to changes in the kinds of issues covered. There is evidence that a lack of coverage of an issue is strongly related to perceptions of unfair coverage. But other data from the Reuters 2021 report suggest that if people think their social and economic class receives too much coverage – possibly because they think the focus should be on less privileged groups or because of inaccurate coverage – perceptions of unfairness can arise. It’s difficult for news organizations to find the right balance.

Loss of gatekeeper role: In the past, if officials or other public figures needed to communicate with the public, they did so through journalists and the media. This is no longer the case. Officials, business people and celebrities now have direct access to the public through social media and journalists themselves are often bypassed. In the absence of journalists, politicians can express opinions or make statements without being challenged or asked to back up what they say with facts. In addition, people, especially younger groups, often get their news from peers who post pictures or descriptions of what’s happening on social media, again bypassing reporters and journalism’s inherent control mechanisms.

This journalism crisis and the struggle for survival has led to a news environment that is decidedly grim – not only in the business offices of media organizations but on their homepages and on the air. The unrelenting fight for attention, clicks, views and shares has turned up the volume and given airtime and headlines to the rudest, loudest voices. The more provocative, the better. Most traditional journalism today focuses on negative events and developments. “Hard” news and “breaking” news reports are generally bad news – crime, political conflict, threats to public health, sex scandals, dire economic forecasts, war, accidents and death. Open the newspaper or website or turn on the nightly news and the public is confronted with a barrage of doom and gloom. The world seems, through this lens, in the midst of a full-scale catastrophe.

The world does contain a lot of bad news, and journalists need to report it. Hiding heads in the sand in the face of unpleasant realities is no solution. But this “negative only” newsroom approach, which has deep roots in journalism history, influences how people see the world. It does so through editorial choices of what becomes news, the framing of stories, the wording of text and choice of images.

“If it bleeds, it leads”: US journalist Eric Pooley is credited with first using this expression in 1989 when he described how the media make use of sensationalism in their headlines and titles. He introduced what became the unofficial mantra that many media houses still follow. It is based on a simple idea: appealing to basic instincts is much easier than appealing to the mind. Sensational, conflict-laden, outrage-inducing stories are better for ratings than news that is nuanced and thoughtful. This reasoning, and some would say race to the bottom, has gained even more influence in a world of increased (digital) media competition and with the advent of social media.

What makes something “news”?: Journalism has long focused on conflict and chaos. In fact, two of the leading “news values”, criteria which for journalists determine if a story is newsworthy, are conflict and negativity. Thus, journalists and editors are accustomed to looking for discord and dispute when looking for stories. The more negative the story, the more exposure it gets. The thinking is: Bad news sells.

Journalism researchers Tony Harcup and Deirdre O’Neill proposed in 2016 an updated set of 15 news values, factors which journalists consider when deciding what is newsworthy and how high up should it go on the page or in the broadcast.

In their content analysis of UK newspapers, “bad news” ranked on top for all analyzed publications (while “good news” landed at position 9). With the increasing use of images, “visual”, “emotions”, and “celebrity” have also become important selection criteria. Considering the changes in the digital age, Harcup and O’Neill assume that editors might also look for “shareability”. When analyzing news stories shared on social media, they found that the most frequently identified values were entertainment, surprise and, perhaps not surprising, bad news.

![]() See Handout 1: Updated News Values

See Handout 1: Updated News Values

More negative in the internet era: Data scientist Kalev Leetaru applied a technique called “sentiment mining” to a BBC Monitoring archive of translated articles and broadcasts from 130 countries between 1979 and 2010. He analyzed the emotional tone of each publication by counting how often positively and negatively connotated words were used, taking into account spikes that reflected specific crises. He found that over the three decades he researched the news had become gloomier. Especially intriguing was the finding that there was a strong plunge toward negativity as online journalism began to take off. Due to increased competition, media outlets apparently more often chose sensational, negative news to capture the public’s attention.

Ever more dramatic and shocking images: Another significant impact of the digital age on news reporting has been the dramatic shift to visual imagery in news items. User-generated images of important world events are now regularly captured on the smartphones of those close to or even directly involved in these events. Media analysts have argued that these kinds of images are presented especially to convey fear, danger, excitement and risk. These kinds of images were not often not permissible or even available to news broadcasters in the past.

Problematic framing: Framing in the media is the angle or perspective from which a news story is told. News is not an exact representation of reality but rather a reconstruction of a small section of reality. Journalists present news in a way that they think makes sense to their audiences, but also using, consciously or unconsciously, their values and judgments or those of their media organizations. A negative frame is often chosen for the reasons discussed above: to increase perceived newsworthiness or get more clicks. Journalists often choose aspects and angles that correspond to their audience’s values, knowledge, interests, and cultural background. This helps to reduce complexity since word counts and air time are limited. But they run the risk of perpetuating negative or overly simplistic ideas, even stereotypes, especially when reporting on foreign countries and cultures.

Media owners, editors and journalists aren’t completely to blame for all the negativity. This focus on the dark side seems to be hard-wired into human beings. People tend to react faster and stronger emotionally to negative than positive events, often spending more time ruminating over problems than contemplating successes, and remember insults better than praise. This is in part due to what are called cognitive biases, systematic errors in thinking that occur when people process and interpret information about the world around them. These biases, which are often a result of the brain’s attempt to simplify information processing, affect the decisions and judgments that people make.

Negative news may influence our thinking through multiple mechanisms. When people see, hear or read something, their brains automatically activate related ideas for a short time. This so called “priming effect” of our unconscious memory is the underpinning bedrock for some cognitive biases:

While the media’s focus on the nasty and negative in the world might result in more clicks or views, this barrage of bad news can have a direct impact on the well-being of audiences and even societies in a number of ways:

Negative effects on mental health: There is growing evidence that negative news can affect our mental health, notably in the form of increased anxiety, depression and acute stress reactions. Research at the University of Pennsylvania (US) found a direct correlation between exposure to the news and depression and anxiety. News consumption often leaves people in fight-or-flight mode – ready to attack the other side (polarization) or wanting to simply hide under a blanket (news avoidance).

The permanent consumption of negative news can increase immobilization and apathy and lead to what psychologists call learned helplessness, a lasting feeling of powerlessness.

| The COVID-19 pandemic has had a major effect on the lives of audiences worldwide and increased feelings of isolation and anxiety. To cope with the “Coronavirus stress syndrome”, experts strongly recommended taking breaks from watching, reading or listening to news stories, including those on social media. |

Reality vs. perception: Journalism acts as a filter between reality and people’s perception of reality. Surveys have repeatedly shown a huge gap between facts and populations’ perception of facts, often due to what they see in the media. When watching, reading or listening to the news, people come away believing that the world is rapidly descending into chaos, even though many aspects of life have improved dramatically over the last few decades.

| For example, in the 1990s news programs in the US tripled their coverage of crime, especially murders, at a time when the murder rate was plummeting. This led people to believe that danger of their being murdered was much higher than it really was. |

The Ipsos MORI market research firm’ Perils of Perception surveys highlights the misperceptions about crime, violence, sex, the climate, the economy, etc. among people in dozens of countries around the world. Every country surveyed overestimates the proportion of people who die through interpersonal violence each year. The average actual figure across all countries is just 1% when the average guess was 8%. Nearly every country in the study overestimates the proportion of people who die annually from terrorism or conflict. The average across all countries is just 0.1% when the average guess was 5%.

Misled by headlines: On social media, the internet and network news, people often only read the headline of a story, then post that information (mentally in their own heads or on social media) as if it were fact. But often the headline doesn’t reflect the facts presented in the story. Media consumers must discern what the real story is, sometimes needing to check other sources to find out. Psychologists like Maria Konnikova have shown that a headline can affect how knowledge is activated in our heads and that it can influence the audience’s framing as well as what people will take away from a story. The headline matters, and media organizations tend to exaggerate them to grab attention on the crowded playing field.

Global misconceptions: This distortion of the state of the world in general was also brought to light by Hans Rosling, an advisor at the World Health Organization. He started testing people’s knowledge about key global health figures and discovered that most people were not aware of the tremendous improvements that had been made over the last 30 years. In 2005, he co-founded the Gapminder Foundation and developed knowledge tests around the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals to fight these misconceptions. In 2018, Time Magazine from the US launched “The Optimists”, a collection of articles edited by Bill Gates highlighting that the world “as a whole” had become “a better place”. Indeed, indicators like child mortality (report from UNICEF) and extreme poverty (figures from Development initiatives) show that great positive strides have taken place, although many people think less about the positive developments than they do about the negative ones (negativity bias).

Disengagement/political apathy: As people tune out from the news, they tend to become less engaged members of their communities and their country’s electorate. Research has revealed that exposure to negatively framed news makes people less likely to take positive action than news stories that take a more positive approach. A study at the University of Southampton discovered that presenting news in a negative way led to “disengagement, avoidance, negative mood and anxiety” among those in the trial. The more negatively people felt after consuming a news story, “the less likely they were to voice their opinions or take actions to make the world a better place.”

Studies in the US have found that news avoiders are less inclined to vote. University of Minnesota researcher Benjamin Toff asks whether the current news environment is conducive to creating an electorate which can hear the other side, can think through complicated political issues and understand a variety of perspectives, all things which a healthy democracy depends on. If people do not consume news, they are less informed, less likely to vote, and potentially more likely to fall under the sway of a populist movement or politician.

Appetite for smash-the-machine change: David Bornstein and Tina Rosenberg, founders of the Solutions Journalism Network, are convinced that the reason Donald Trump won the 2016 elections was because he benefited from journalism’s steady focus for decades on what was going wrong in the country. The somber picture – darker than statistics justified – allowed the seeds of discontent and despair that Trump planted take root, they wrote in the New York Times. “One consequence is that many Americans today have difficulty imagining, valuing or even believing in the promise of incremental system change, which leads to a greater appetite for revolutionary, smash-the-machine change.” This kind of “throw the crooks out” attitude and violent fervor was on full display in the January 2021 attack on the US Capitol by a group largely made up of Trump supporters.

Effects on journalists and journalism: Let’s not forget the people behind the negative headlines, many of whom have something of an image problem. Journalism is regularly ranked among the most unpopular professions. Journalists are often criticized for exaggerating an issue, for not dealing with problems faced by “real people” or for increasing polarization to get clicks or viewers. It’s an ironic situation since many journalists see their mission as a noble one, which seeks to do good and help society.

In addition, numerous studies have shown that the mental health burden on journalists can be a heavy one. Reporting on conflict, traumatic events and disaster leaves a mark; burnout is not uncommon. Of journalists who covered a powerful hurricane in Texas in 2017, two in five “met the threshold for depression” and 93% had symptoms of depression. For journalists reporting on COVID-19, the stress has been even higher than normal. Several studies, including one from Reuters, showed that a significant number of journalists reporting on the virus exhibited signs of anxiety and depression. A different approach to the news could benefit media practitioners as well as media consumers.

What can the media do to turn the tide? As audiences, particularly young people, lose their connections with traditional media, media organizations are intensifying audience research in an effort to find out what audiences want in order to keep them interested or bring them back.

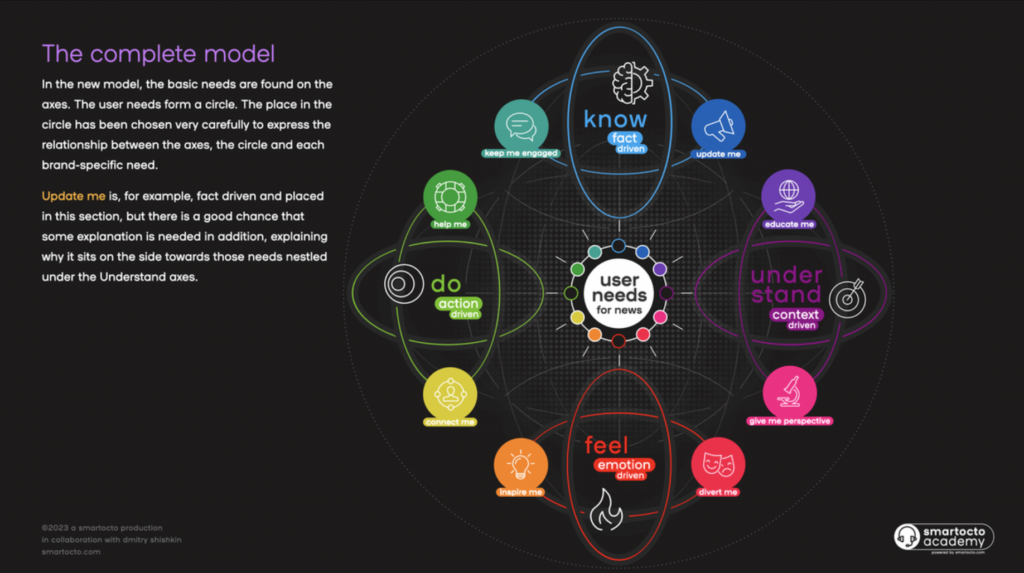

More than updates: Audiences around the globe want to be updated on events in their countries, their regions, the world. But they also want more. A large-scale, multiregion BBC study from 2016 identified five other important audience needs: “give me perspective”, “educate me”, “keep me on trend”, “amuse me” and “inspire me”.

Dmitry Shishkin, former digital development editor at BBC World Service

Other needs neglected: The BBC team then analyzed three months of its output across languages and found that 70% of its content contributed to “update me”. The broadcaster then concluded that if BBC programs were to reach younger audiences, they would need to address these other needs in a more balanced way. The BBC Next Generation survey from 2016 confirmed that a large majority (64%) of young audiences (under 35) in emerging economies want news to also provide solutions to problems, moving beyond simply covering what has happened to also discussing where to go next.

Desire for new perspectives: DW audience research in Kenya (2019) revealed that viewers are frustrated by the way African stories are covered by broadcasters. International outlets focus on disasters and problems without showing solutions; local ones focus on local events. The audience appreciated that the stories by DW News Africa were told through the eyes of people on the ground and reported on negative events without showing grisly footage. Nevertheless, some viewers criticized single reports for lacking a solution-oriented approach as well as different points of view. The target group wanted more reporting on underrepresented or neglected issues, a bigger variety of topics, and stories that were empowering. Other DW acceptance studies from countries across the globe have shown that audiences want a more nuanced and constructive approach to coverage.

Inspiring stories drive readership: In 2019, an audience research team at the fashion magazine Vogue (2019) surveyed 3,000 loyal readers and another 2,000 people who don’t read the publication but are interested in fashion in different American, Asian and European countries. The researchers identified six reader needs: “inspire me”, “educate me”, “divert me”, “update me”, “make me responsible” and “connect me”. Of all the stories published by Vogue in one month, 38% met the need “‘update me”, 26% “divert me”, 21% “inspire me”, and just 2% “make me responsible”. They also found that “inspire me” stories had the highest average readership, while “update me” stories scored the lowest.

© smartocto collab. Dmitry Shishkin

Upgraded user needs model: The digital publishing consultant Dmitry Shishkin took the BBC model (internally known as “Dima’s wheel of news”) to many newsrooms in the Global North and South. Based on his experiences, the company smartocto created an upgraded version of the famous BBC model (March 2023). It maps user needs on four axes of basic audience needs: “know – understand – feel – do”. The biggest departure from the previous model is the inclusion of this last category of action-driven news that provides content to make their users’ lives easier. The model takes into account that the solutions-focus has become more important in news production. It introduces two new user needs: “help me” and “connect me”, and “keep me on trend” has been replaced by “keep me engaged”.

The evolution of audience-driven news publishing seems to become a trend. This is at least what Nic Newman, the author of the RISJ 2023 annual trends report, predicts: “This year, we can expect more examples of user needs model driving news product development, not just content commissioning.” According to a survey among publishers from different parts of the world, most of them (72%) are worried about increasing news avoidance. They say they plan to counter this with explainer content (94%), Q & A formats (87%), solutions/constructive journalism (73%), inspirational stories (66%) or broader agenda (65%).

![]()

Journalism faces a crisis in trust. Journalists fall into two very different camps for how to fix it

www.niemanlab.org/journalism-faces-a-crisis-in-trust-journalists

“From Negative Biases to Positive News: Resetting and Reframing News Consumption for a Better Life and a Better World”

www.repository.upenn.edu/From-Negative-Biases-to-Positive-News

Academic who defined news principles says journalists are too negative, The Guardian, 2019

www.theguardian.com/world/2019/news-principles

Our world in data

www.ourworldindata.org

www.sdg-tracker.org

Shayera Dark, Lagos: Selling Africa’s good news stories

www.mg.co.za/selling-africas-good-news-stories

If It Bleeds, It Leads: Understanding Fear-Based Media

www.psychologytoday.com/understanding-fear-based-media

Book: Jodie Jackson (2019), You Are What You Read – Why changing your media diet can change the world, Unbound

Steven Pinker, The media exaggerates negative news, The Guardian, 2018

www.theguardian.com/media-negative-news

Don’t let confirmation bias narrow your perspective

www.newslit.org/dont-let-confirmation-bias-narrow-your-perspective