Main topics: Origins of constructive journalism, similarities/differences with other forms of journalism, the journalist’s role, ethics, ethnocentrism, Eurocentrism, potential in the Global South, impact of constructive journalism on audiences.

Summary: Constructive journalism’s origins extend back to the middle of the 20th century, although its concepts have taken on more concrete form over the past two decades. It shares similarities with other forms of journalism, such as conflict-sensitive journalism, restorative narrative and civic journalism, among others, although there are also important differences. Constructive journalism asks journalists to consider what role they will play in society: one that simply monitors or one that takes a more active role – without becoming activists. As influential societal actors, journalists should avoid propagating stereotypes or adopting ethnocentric or Eurocentric perspectives. There is great potential for constructive journalism in the Global South, although there are also risks and potential pitfalls that may vary according to the regional context.

While the name “constructive journalism” is a fairly recent coinage, the approach itself has been around for more than half a century. In 1948, a news service appeared in New York called “Good News Bulletin”. It asked: “Have you had your daily dose of catastrophes, crises and cynicism?” and is considered the first constructive news endeavor. Made up of a few pages and sent out to newsrooms and universities once a week, the bulletin contained information on “successful projects and positive alternatives” and closely followed the newly founded UN organizations such as the WHO, UNESCO and UNICEF. In 1959, David Chalmers published “The muckrakers and the growth of corporate power: A study in constructive journalism”. Even though American muckraking journalists at the turn of the 20th century did not apply the word “constructive” to their work, their approach was to expose societal ills and also to offer ideas how people could overcome those problems. In the 1980s, the terms “civic journalism” and “public journalism” emerged, referring to forms of journalism that share many characteristics with constructive journalism.

Two of the most prominent organizations promoting constructive journalism today are the Constructive Institute (CI), based in Aarhus, Denmark, and the Solutions Journalism Network (SJN), headquartered in New York.

A brief timeline of the constructive journalism movement:

● 1948: “Good News Bulletin” appears in New York

● 1988: terms “civic journalism” and “public journalism” gain currency

● 2004: French NGO Reporters d’Espoirs was created to promote solutions-based news

● 2007: Danish media groups begin experimenting with constructive approaches

● 2013: Solutions Journalism Network founded

● 2017: Constructive Institute founded

Constructive journalism builds on and shares features with other forms of journalism such as peace journalism and conflict-sensitive journalism. It picks up elements from other types as well, such as development journalism (see table below). Constructive journalism can be seen as a broad umbrella for a practice that is conscious about its impact and wants to use it in a responsible way.

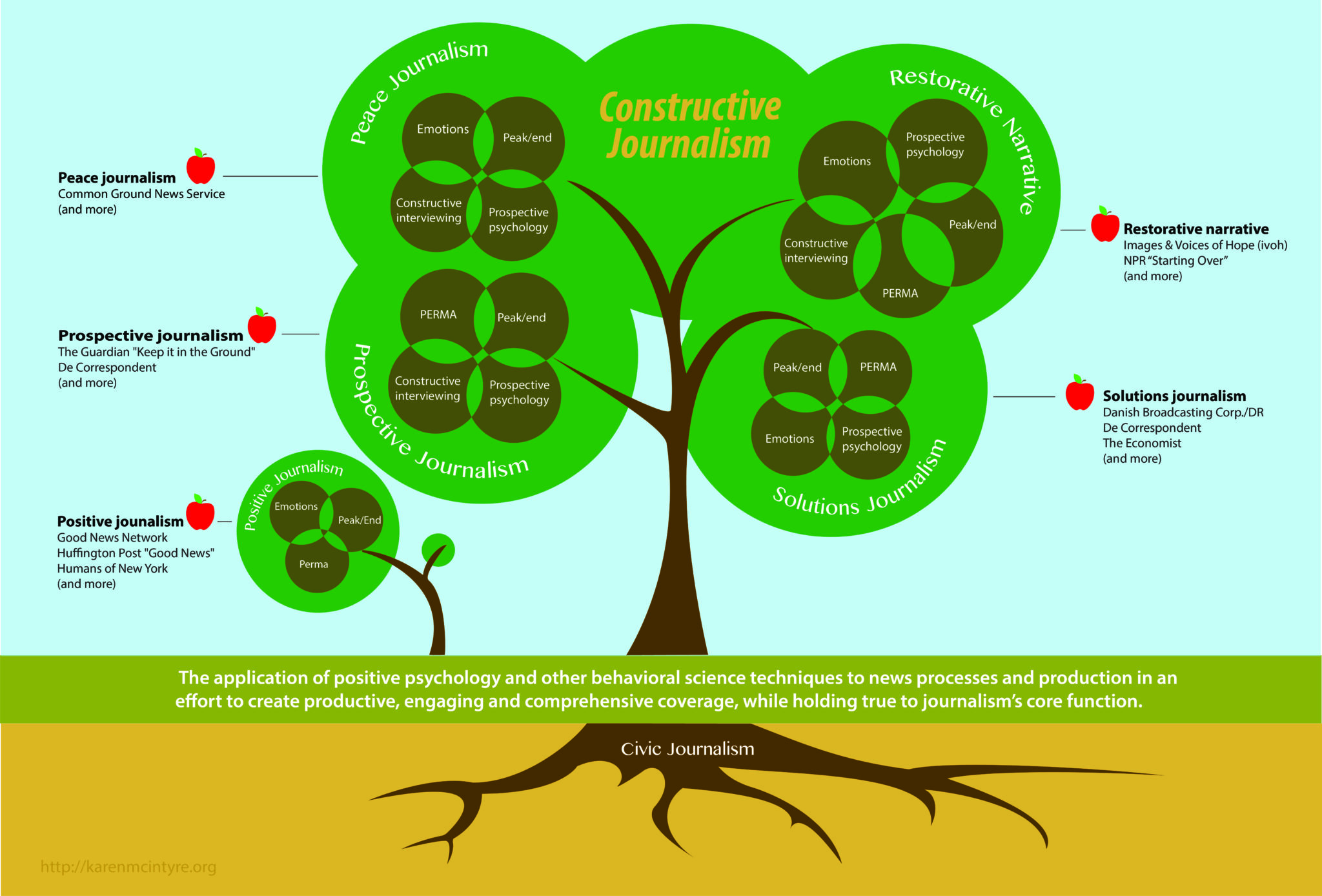

One of the pioneers of constructive journalism, the Constructive Institute’s founder Ulrik Haagerup, has described constructive journalism as a “megatrend” in journalism which would transform the practice of journalism. A 2018 paper by Tanja Aitamurto and Anita Varma argues that constructive journalism should be considered as a “resurgence” and not reinvention of journalism because it is still based on the established norms of journalism. Constructive journalism researcher Karen McIntyre visualizes different forms of journalism as branches of a larger constructive journalism tree:

Source: Karen McIntyre and Catherine Gyldensted

The following chart offers a comparison of various forms of journalism:

Journalism concepts | How they relate (=) or differ (#) |

Service Journalism provides useful and practical advice (pdf) on how to live well. It covers all aspects of everyday life – lifestyle, culture, travel, food, books, technology, money, and fashion, but also features tips on relationships, health, psychology and how to live a considered life. It’s “news you can use” that ranges from the serious to the superficial. | = addresses audiences looking for advice and orientation (solutions) = assumes a social role for journalists # is more oriented towards consumer advice # often blurs the lines between reported news and opinion |

Development Journalism can refer to two different types of journalism. The first type focuses on developing nations and ways to improve conditions there. Journalists look at projects and analyze their effectiveness, even offering proposed solutions and suggesting ways to implement them. A second type involves influence from a government. This can be a tool for local education and empowerment, but also can be used to suppress information and restrict journalists. For example, journalists can be told not to report on certain controversial issues because it will impact the “development” of the nation. | = addresses problems and proposes solutions = aims to empower people to overcome poverty and underdevelopment # specifically relates to the developing world # journalists can take on a more activist role # addresses only development topics such as poverty and inequality # can be “hijacked” by governments (second type) |

Community Journalism operates traditionally in small geographic markets and emphasizes local news and information. Most community journalists are professionally trained reporters and editors, not citizen journalists. Journalists working in this mode tend to develop a closer, more intimate connection to the community they serve. In a broader sense, community journalism can also address non-geographical communities, such as professional or special-interest communities, in the real or virtual world. | = aims to engage targeted audiences in its news production cycle = tends to cover subjects that larger news media might not # addresses specific audience segments rather than the public at large # is not specifically centered around a solution-based approach # reporters do not always maintain objective distance from stories they cover |

Restorative narrative provides stories of resilience and recovery within communities in the wake of traumatic events or longstanding problems (Examples: Rwandan genocide in 1994; the Beirut port explosion in 2020). Restorative narrative is supposed to inspire audiences and give hope for healing and growth. The reporting often requires a long-term commitment from journalists. But by telling more complete and authentic stories, proponents say confidence and trust in storytellers is increased. | = aims to present contextual reporting and to explore societal remedies = focus is on how people move on (resilience) after adversity instead of just describing the difficulty faced = aims at “the social good” # relates to specific situations/events instead of a general approach |

Solutions Journalism is rigorous reporting about responses to social problems. While holding true to core journalistic standards, it investigates and explains, in a critical way, examples of responses to problems that are being tried out. Solutions Journalism explores the effects of these responses and examines their sustainability. It offers interview techniques that “complicate the narrative” by getting at underlying motives and interests, thereby finding root causes of disagreement and possibly decreasing polarization. | = Forward looking = a nuanced representation of reality = critical, data-based journalism = techniques to discuss controversial topics # focused on solutions |

Peace Journalism reveals background information of conflicts, places events into their wider context, casts light on all sides and explores peace initiatives and ideas. According to the Media Peace Project, Peace Journalism “gives peacemakers a voice while making peace initiatives and non-violent solutions more visible and viable.” It often tends toward advocacy for peacemakers. It seeks to facilitate dialogue in conflict and post-conflict contexts. | = strong constructive elements = high ethical standards = oriented towards solutions for a peaceful future = promotes dialogue and mutual understanding # limited to a specific context of conflict and war |

Conflict–Sensitive Journalism involves in-depth, fair, accurate and responsible reporting on conflicts without feeding the flames. It explains the multiple perspectives of involved parties, the causes and context of conflict, and examines possibilities for peacebuilding while showing the human face of conflict. Conflict-sensitive media practitioners report on responses to conflict and possible solutions. Their role is not to reduce conflict themselves but to encourage peace-building processes (.pdf). Conflict-sensitive journalism does not engage in advocacy but is constructive and peace oriented. | = constructive approach by contributing to consensus building, decreased polarization and resolution of conflict = high ethical standards, avoids stereotypes = corrects misconceptions = balanced and responsible # limited to a specific context of conflict and war |

Civic journalism (or public journalism) uses a bottom-up approach and prioritizes non-elite sources to set a “citizens’ agenda”. It addresses people as participants in public affairs, rather than as victims or spectators and aims to include the public more in the information- gathering process. Its goal is to help the community act on problems and improve the climate of public discussion. | = seeks to engage and empower audiences = aims to encourage positive action on the part of the public = aims to create public debate = sees a different role for the journalist # has been criticized for not being objective and for creating activist reporters |

Positive Journalism focuses on good news and inspiring stories. They are often uplifting. This form often has less rigor than investigative or traditional journalism and stories are often about heroes and individual events that often have less significance to society at large or do not offer systemic and replicable responses to problems. | = reports on what is working in society = stories can offer inspiration and feature role models # often lacks in-depth reporting or a critical viewpoint # tends toward light, “soft” news |

Journalists are traditionally taught to be witnesses – present the facts and those facts will speak for themselves. But that approach is too restrictive, say constructive journalism proponents, and not even all that effective anymore. It’s not enough to simply tell the public what’s going on in their communities or the wider world, but people also need to understand why something is happening, how it got to this point, and how they can make informed decisions to affect the outcome. While most journalists see their job as holding up a mirror to society, if they fail to cover the ways people and institutions are succeeding or at least trying to, they are leaving out an important part of the picture.

The collapse of traditional business models and intense competition in digital markets have forced many media companies to put a strong focus on earning advertising revenue. This hunt for clicks attracts audiences via sensationalism and measures its impact through hard numbers. Constructive journalism, on the other hand, wants to be measured on societal impact as well as on revenue generation.

In the end, journalists, editors and media organization owners have to decide if they want to feature the most dramatic, fear-inducing stories to reach their performance goals and get clicks and likes. That might work in the short term, but at what cost? Or do they also want to highlight opportunities, fresh perspectives, ways out of difficulty and reasons for hope? This latter approach can arguably keep audiences more loyal over the longer term.

Many journalists, especially experienced ones, have work habits and philosophies that are deeply ingrained. Talk of taking on a more active role in reporting and being something besides a disinterested observer is not a role that all journalists are comfortable with. But constructive journalism does not seek to change the core mission of journalists. They should still be concerned with hard facts, uncovering problems and asking critical questions. But constructive journalists also ask themselves: What can I do to respond to this problem?

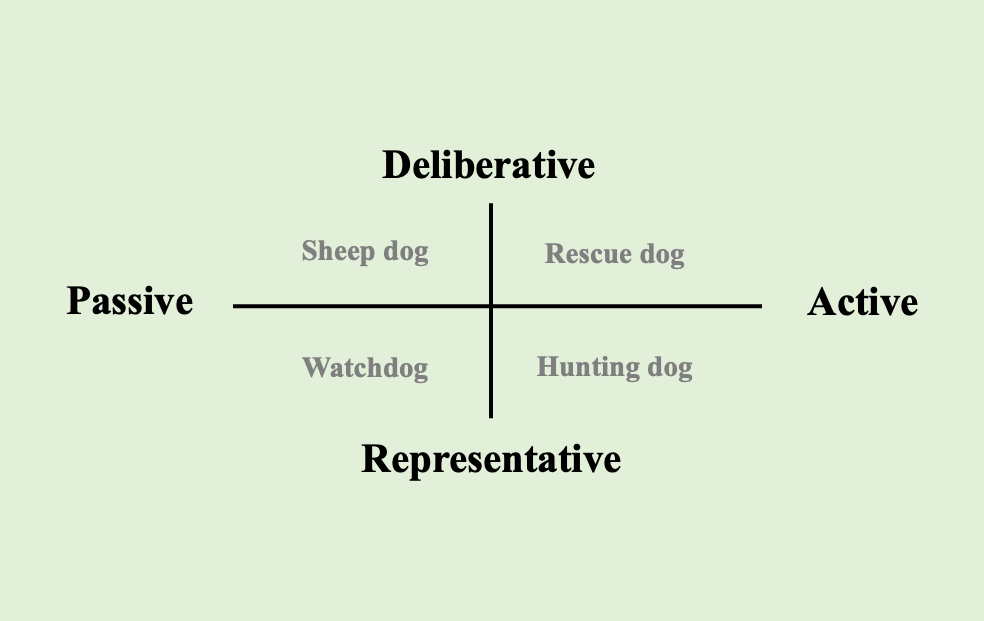

“Breeds” of journalists: In a complex world that faces serious, even existential challenges, many journalists, younger ones especially, want to play a more active role in society. Are journalists simply watchdogs, exposing wrongdoing and criticizing before moving to the next story? Or should they act as “guide dogs” as well, taking on a more active role as arbitrators in the public debate about responses to challenges, enabling dialogue and engagement, and presenting events and issues in all their complexity? The following “Action Compass” looks at the roles of the journalist from a canine perspective.

Source: The Action Compass, Peter Bro, Journalistica 2006

Watchdog: Most journalists are taught to be witnesses and adopt a monitorial role that holds a mirror up to society and holds the powerful to account. They spread knowledge to help their audiences understand issues and enable them to make informed decisions.

Sheep dog: Journalists can also adopt a facilitating/moderating role and offer a platform for public dialogue.

Hunting dog: Journalists in this category also look at problems, like watchdogs, but also confront those in positions of power about how they would solve those problems.

Rescue dog: Journalists of this category actively seek to inspire, encourage and create positive change in society. Constructive journalists see themselves in this category while still taking the monitoring and facilitating role seriously. They see their role as:

A note on activism: Although constructive journalism facilitates dialogue, mutual understanding and solution finding there is a line between it and advocacy or activism. This line can be hard to identify and often needs to be discussed on a case-by-case basis. Most traditional journalists are opposed to being seen as activists and any way, shape or form. But there is an argument that journalists cannot stay completely neutral on certain subjects, such as climate change, genocide and discrimination. In general, constructive journalism does not call on journalists to become activists. When they are pursuing solutions stories, the journalists should not become advocates for one particular solution or promote a solution they have come up with themselves. They still should report on both the positive and negative sides of any response. But it can be a tricky line and some worry it is easy to cross over from observer to advocate and activist.

Some media organizations are more open to blurring that line, especially on climate change. There are reporters who describe themselves as activists, who even prepare impact strategies and campaigns alongside interest groups. This might be justifiable, but it falls outside the principles followed by constructive journalism as we define it.

Constructive journalism acknowledges its impact on society, therefore journalists have an even increased ethical responsibility to consider the different ways in which their work influences and changes perceptions and public conversation. Journalists and filmmakers can either be a vector of bias or a victim of stereotyped representations. How can they show the most accurate picture of the world and avoid reproducing stereotypes and an ethnocentric perspective?

Ethical awareness of choices: Constructive journalists should be particularly aware of their framing and choices. They should reflect on the ethical consequences these choices might have. For example, the language they use, the points of view they adopt on the one hand and the visual language, music and editing style on the other. They need to be fully aware of their ethical responsibility towards the people they are portraying or reporting on as well as towards their audiences.

Harmful stereotypes: Stereotypes are oversimplified and widely held beliefs about certain people or groups. They are often related to ethnicity and gender. Many studies show that the most affected groups are minorities, women and vulnerable populations. In her famous TED talk in 2009, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie described the danger of a single story: “Show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again and that is what they become.” Research confirms that simply knowing that there is a negative stereotype against a group, can lead individuals who belong to this group to perform more poorly than they normally would.

● The Middle East: This region has been portrayed by US and other international media outlets in the past as a region “trapped in an eternal cycle of violence, instability and terrorism. Everyone is Arab and Muslim, oppression of women is ubiquitous, and Shias and Sunnis have always and will always hate each other.” The complexity of the MENA region with its rich traditions is quite often ignored or oversimplified by global media outlets.

● Africa: The continent is quite often portrayed as war-torn, disease-ridden and poverty-stricken. In the Columbia Journalism Review, Karen Rothmyer who lived in Kenya for several years, traced the endless stream of bad news to Western NGOs and aid groups’ depiction of the severity of problems on the continent and work to be done there in order to justify their existence and keep donor funds flowing. This, in turn, helped shape Western reporters’ “frames of reference” before they even arrived on the continent.

● South Asia: This subcontinent is often depicted as dirty and chaotic, marked by sectarian conflict and crushing poverty. Or, it is the home of a thriving information technology industry and glittering film productions. It’s often praised as a promised land of exoticism and mysticism, where westerners travel in search of spiritual awakening. For many in the Global North, South Asia is a land of both revulsion and fascination, the giant slum or the Taj Mahal, where nuance and an accurate reflection of its diverse reality are lost.

Gender stereotyping: This is one of the factors behind unequal pay, domestic violence, femicides and all forms of violence against women. It is violence that female journalists increasingly have to deal with, especially online. A survey conducted with 600 women media professionals shows that the three main areas of concern for female journalists are direct harassment, invasion of privacy and denial of access. According to the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) “Nearly two out of three respondents said they had been threatened or harassed online at least once” in the last year. Apart from psychological effects, respondents reported professional consequences; many abandon the pursuit of specific stories (self-censorship) and some even consider leaving the profession entirely. Freelancers feel the least safe. IWMF and the TrollBusters network provide practical resources such as training and/or rescue services.

Gender-sensitive indicators: UNESCO offers a guide for journalism educators to explore gender-related biases, stereotypes and sensitivity before teaching about the representation of others. This guide (available in English, Arabic, French) focuses on two areas: How to improve gender portrayal in media content and how to foster equality within media organizations and journalism schools.

High ethical risks at post-production stage: Africa No Filter published a handbook on ethical storytelling. A study revealed that especially “at post-production stage, poor time planning can lead to rushed and sloppy editing, which has ethical implications.” Reporters in the MENA region complain that post-production is often done by other colleagues who are unfamiliar with the protagonists and situation on the ground. By spending more time with a community, storytellers could get to know them better and see them in a different light, which allows “you to tell a different story, which will not repeat the same old stereotypes.” The handbook’s main recommendations:

● Create better, more authentic stories that connect people of different backgrounds and disrupt inequitable power relations, such as those around race, gender, ethnicity and sexuality.

● Represent lived experiences more accurately.

● Encourage mutual respect.

● Preserve the dignity of those whose story is being told.

Ethnocentrism: Humans tend to view their own culture as the standard by which to evaluate other ones. Ethnocentrism is an expression of cultural identity and a natural condition experienced by all cultures. Media professionals are both influenced by ethnocentric assumptions and contribute to the formation of ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism plays a significant role in how news is reported, as well as what news is reported. The danger of ethnocentric framing and reporting is that it creates and reproduces stereotypes. This can become particularly harmful in a context of conflict or war.

Eurocentrism: The US online dictionary Merriam-Webster defines Eurocentrism as “reflecting a tendency to interpret the world in terms of European or Anglo-American values and experiences.” Eurocentrism cannot be seen as “just another ethnocentrism” as it is common even in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and many parts of Asia. European colonial expansion resulted in the formation of “a colonizer’s model of the world” and “historical tunnel vision”. Countries in the Global South “know virtually nothing about each other – and if they do, the knowledge they possess comes from Western sources.” For the political scientist Oliver Della Costa Stuenkel, the terms “West” and “non-West” show how Western-centric our thinking has become. “In fact, dividing the world between West and non-West is even less useful since the definition of the West has changed over time, and there is no consensus about who is and who is not part of the West. Just think of whether Australia, Mexico, Israel, Ukraine, Georgia, Greenland or Brazil are part of the West or not.”

Example: When reporting on the “refugee crisis” in 2015, many news outlets fueled xenophobia by rendering the masses of refugees as an approaching threat. A less Eurocentric view could try to contextualize the so-called crisis within Europe’s colonial past or explore the benefits of the constant migration that the continent has experienced for generations.

There is still a limited amount of scientific research on constructive stories’ effects on audiences, but there is some – mostly out of Europe and North America – which have shown encouraging results.

Boosted perception of article quality and interest in issue: The Center for Media Engagement (University of Texas, Austin) conducted a 2019 study to determine how certain components of solutions journalism affect the way readers evaluate both the reporting and the issue. It found that articles that included all components of solutions journalism (problem/solution, implementation, results, insights):

● Improved readers’ perception of article quality.

● Made readers more likely to “like” a similar article on Facebook.

● Increased readers’ interest in and knowledge about the issue.

● Increased intentions to read more articles about the issue.

● Boosted readers’ positivity.

● Led readers to believe there were ways to effectively address the issue.

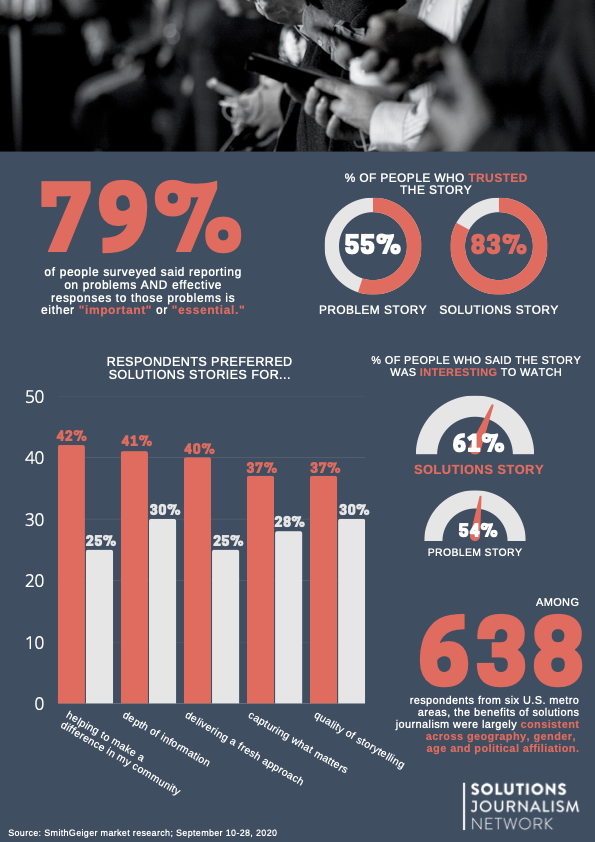

Preference for solution stories: Further evidence comes from the US market through a 2020 audience engagement survey done by the Solutions Journalism Network and Smith Geiger around TV coverage. The study analyzed the preference of the audience for solutions-focused reports compared to problem-focused pieces on the same issue. Solutions-focused stories scored higher in every metric.

Source: Solutions Journalism Network, SmithGeiger market research, 2020

Paying off for the media and societies: A 2021 study by the Grimme Institute in Germany found that people were looking for constructive stories, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. This interest led to a small boom in solutions-oriented and constructive formats – people were interested in useful and solutions-oriented journalism geared to their daily reality. The study also found that constructive journalism can increase the proximity between media and audiences, which in turn can strengthen people’s trust in media. Increased trust is an important prerequisite for monetization within subscription or membership models.

![]() See Handout 6: A more in-depth look at the impacts of constructive journalism

See Handout 6: A more in-depth look at the impacts of constructive journalism

![]()

Journalists’ perceptions of solutions journalism and its place in the field (Knight Center)

www.isoj.org/journalists-perceptions-of-solutions-journalism-and-its-place-in-the-field

Impact as driving force of journalistic and social change

www.thebureauinvestigates.com/blog/2018-01-19/reflections-on-our-2017-impact-report

How to build impact: a case study

www.medium.com/how-journalists-can-achieve-bigger-impact-with-their-stories

Strategies for tracking impact – A Toolkit for Collaborative Journalism (.pdf)

www.google.com/amazonaws.com/Impact_Guide.pdf

The Constructive Role of Journalism

www.researchgate.net/publication/The_Constructive_Role_of_Journalism

Constructive journalism: Why and how journalists want to change the rules

www.dw.com/constructive-journalism-why-and-how-journalists-want-to-change-the-rules

Constructive Journalism in the Egyptian Context: Roles and Challenges (.pdf)

www.qu.edu.qa/Constructive-Journalism-JMEM2018.pdf

Identity, Contingency and Rigidity: The (Counter-) Hegemonic Constructions of the Identity of the Media Professional, Carpentier, N. (2005)

www.researchgate.net/Identity_contingency_and_rigidity

Ethics:

SPJ Code of Ethics

www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp

Photography, Photojournalism, Editing, & Ethics

www.digitalphotosquad.wordpress.com/photography-photojournalism-editing-ethics

What to Do About Documentary Distortion? Toward a Code of Ethics

www.documentary.org/feature/what-do-about-documentary-distortion-toward-code-ethics

Stereotypes:

Amnesty International, Look beyond borders – 4 minutes experiment, 2016 campaign

www.youtube.com/Amnesty-International-Look-beyond-borders

What Makes Nuanced Portrayal? Avoiding the unconscious stereotype trap

www.ipsos.com/what-makes-nuanced-portrayal-avoiding-unconscious-stereotype-trap

Gender stereotypes in journalism

www.conseilsdejournalistes.com/en/egalite-genre/10-les-stereotypes-de-genre-dans-le-journalisme/

Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People

www.jstor.org/stable

Diversity quiz, developed by Human Library, a non-for-profit learning platform challenging stigma and stereotypes

www.humanlibrary.org/new-diversity-quiz-to-help-us-unjudge

Tara Ross, Alexandra Wake and Pascale Colisson, Stereotyping and Profiling, 2020 – about educators’ responsibility (.pdf)

www.journals.sagepub.com

Eurocentrism:

Africa no Filter

www.africanofilter.org/research-how-african-media-covers-africa

The “Refugee Crisis” as a Eurocentric Media Construct: An Exploratory Analysis of Pro-Migrant Media Representations in the Guardian and the New York Times

www.triple-c.at/index.php/triple

Is it possible to decolonize the media? Power dynamics filter into the journalistic method and ultimately alter — however subtly — what news is consumed and by whom.

www.poynter.org/ethics-trust/2021/is-it-possible-to-decolonize-the-media

Decolonizing Communication Media and Digital Technologies

www.ritimo.org/Decolonizing-Communication-Media-and-Digital-Technologies

Neuliep, Hintz, & McCroskey, The influence of ethnocentrism in organizational contexts, 2005 (.pdf)

www.jamescmccroskey.com/publications/210.pdf

Angela Romano, International Journalism and Democracy – Civic Engagement Models from Around the World, 2010 (book)